What You Hack Is What You Mean: 35 Years of Wiring Sense into Text

Computers can’t do much without encoding. They need ways to turn bytes into symbols, words, and meaning — to make text readable for both humans and machines. But encoding isn’t just for machines. Humans also encode: we describe, structure, and translate our thoughts into text. And while the number of text formats seems endless (and keeps growing), that’s not a bug — it’s a feature. Diversity in encoding is how we learn what works and what doesn’t.

Long before ASCII tables or Unicode, text encoding already existed — in alphabets, printing presses, and typographic systems. Every technology of writing has been a way of hacking language into matter: from clay tablets to lead letters, from code pages to Markdown. Each era brings new formats and new constraints — and with them, new genres, new rules, new cultural codes. Think of poetry and protocol manuals, fairy tales and README files, the Hacker Bible itself — all shaped by the tools and conventions that carry them.

So here’s the question: can we encode not only what we see, but what we mean? Can we capture a poem’s rhythm, a play’s voices, or the alternate endings of a story — and do it in a way that’s open, remixable, and machine-readable?

Turns out, yes — and the solution has existed since 1988. It’s called the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI), a long-running open-source standard that lets you describe the structure, semantics, and context of texts using XML. You can think of it as a humanities fork of hypertext — an extensible markup language for everything from medieval manuscripts to memes.

TEI is more than a format: it’s a collaborative, living standard maintained by an international community of researchers, librarians, and digital humanists. It evolves with the world — adding elements for new text types (like social media posts) and for changing cultural realities (like non-binary gender markers). It embodies open science principles and keeps publishing in the hands of its creators.

You don’t need a publisher, a platform, or a big server farm. Just an XML-aware text editor, a few lines of CSS, and maybe a Git repo. From there, you can transform your encoded text into websites, PDFs, e-books — or share it directly in its raw, readable, hackable form. It’s sustainable, transparent, and low-energy. It even challenges the academic prestige economy by making every individual contribution visible — from editors to annotators to script writers.

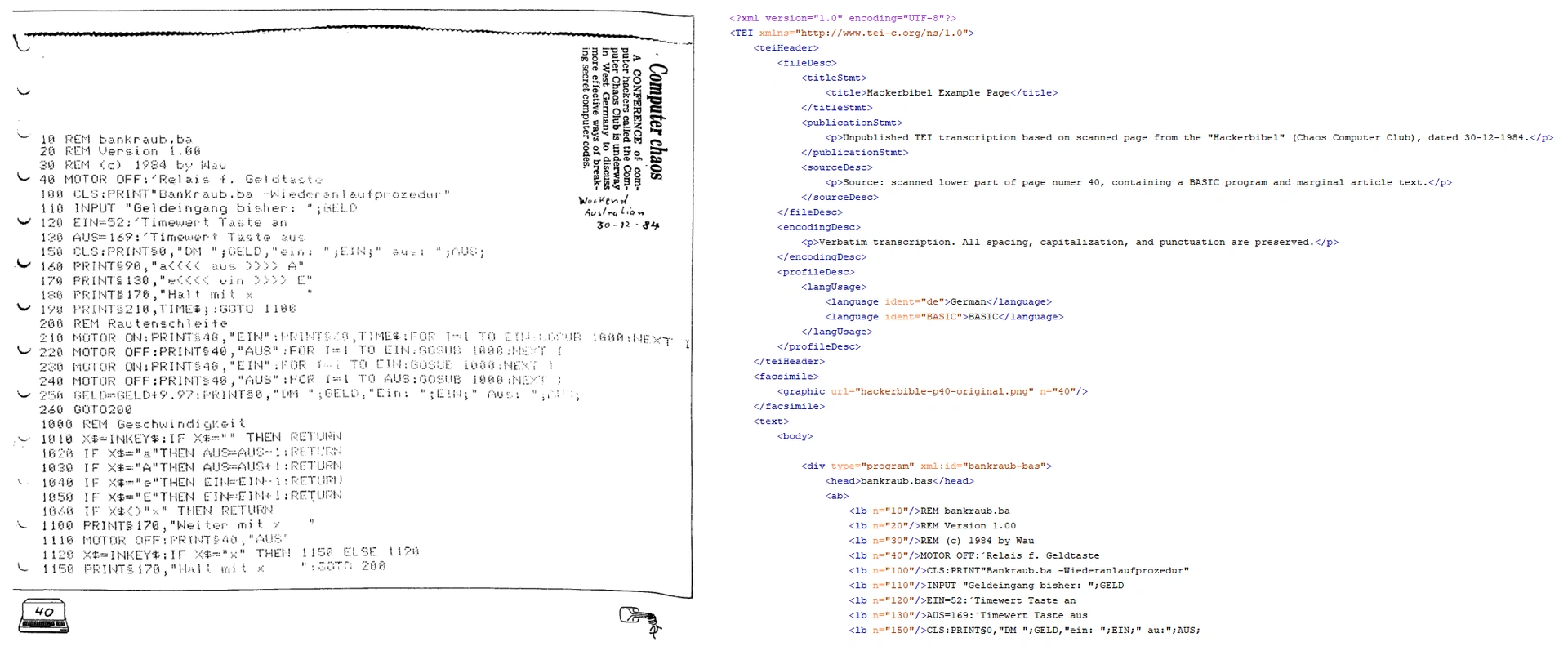

In this talk, we’ll look at text as code and code as culture, from alphabets to XML, and explore how TEI can be a tool for hacking not machines but meaning itself. We’ll end with a practical example: a TEI-encoded page of the first Hacker Bible — because our own history also deserves to be archived, shared, and forked.